The Value of Storytelling

It was a terrific honour for me a few weeks back to get nominated for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award 2014. This is an international award that is open to children’s writers and children’s illustrators and also to oral storytellers. Based in Sweden, it’s the biggest such award in the world and, of course, it was set up in memory of the creator of Pippi Longstocking who also wrote many other now-classic children’s tales.

So far, no oral storyteller has won the Astrid Lindgren Award. How wonderful it would be if I did – not because I personally crave or deserve such a thing but because it would give such tremendous impetus to the cause of oral storytelling.

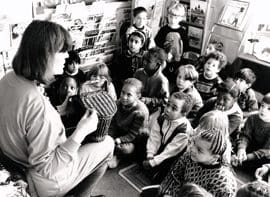

Oral storytelling is again in decline in education. After the huge boost that was given to it by the National Oracy Project in the 1980s and by all the subsequent attention to Speaking and Listening in Early Years and Primary schools, it is now suffering from budget cuts, curriculum pressures and emphasis on targets. Yet for adults working with children – let alone for the children themselves – oral storytelling is an acknowledged key to bringing about a whole new kind of excitement and confidence about story. Children really listen to told stories. If you’re the teller, that can only be good for your own self-image. For the children, it can have the corresponding result of increasing their concentration and imagination. When a story is orally told, maybe with sound effects and actions, it makes the children look directly at you. It also inspires their responses and makes them really keen to listen, speak, write and draw.

So if you’ve never done it before, this is am excellent time to start. At the beginning of a new school year, fresh thinking is what everyone needs. So why not think about starting with a story you already know pretty well? (Goldilocks? Three Billy Goats Gruff?) Check your memory of the story with the book. Then set the book aside. Tell the story to yourself in your mind, not by remembering the exact words in the book but by thinking about it in your own words and with your own mental pictures. When you feel you’ve got it, try telling the basic plot to your partner, children at home or a friend. Next, tell it to the children you work with. Don’t worry about being nervous. Being nervous is OK. Anyway, there’ll be plenty of other chances if you don’t do so well the first time you try it. Try it again another day (children respond better when a story is repeated) and instead of thinking about yourself, observe the children’s responses. Note what bits you and they enjoy and in a day or two, try it again. Maybe add a prop or two (but nothing complicated to distract from the telling).

After you’ve taken your initial step of telling a story once and again, it’s time to start thinking about how to really open up a story to the children, perhaps by pausing on places in the story where other things could happen that they might like to talk about, perhaps by getting children to make pictures of the story after you’ve finished and then maybe bringing these together in a class book. The possibilities are endless.

And, of course, that’s only your first told story. There can be so many more. As you go on, you’ll start to realise the enormous power of oral storytelling as a way of developing literacy. It’s also the best possible way to develop children’s thinking about social and moral issues.

Oral storytelling does not replace books and reading. It goes along beside them. This is why, a week or two ago, it was so good to read a Guardian interview with the well-known author Philip Pullman (himself an early winner of the Astrid Lindgren award). The interview was occasioned by the upcoming publication in paperback of Grimm Tales for Young and Old, his retelling of 50 of the Brother Grimm fairytales. In it, Pullman took the opportunity not only to urge adults to read stories with children but also, because of the power of it, to tell stories orally to them. As someone who used to do exactly that when he himself was a schoolteacher, he knows the truth of what he’s saying. I hope it’s a truth that can once again start to spread.

Mary publishes a weekly storytelling Blog. It can be accessed from her website: www.storyworks.org.uk.

Popular Teaching Resources

Stay Up To Date

Sign up for our newsletter and we’ll let you know when we create new early years resources.

Comments